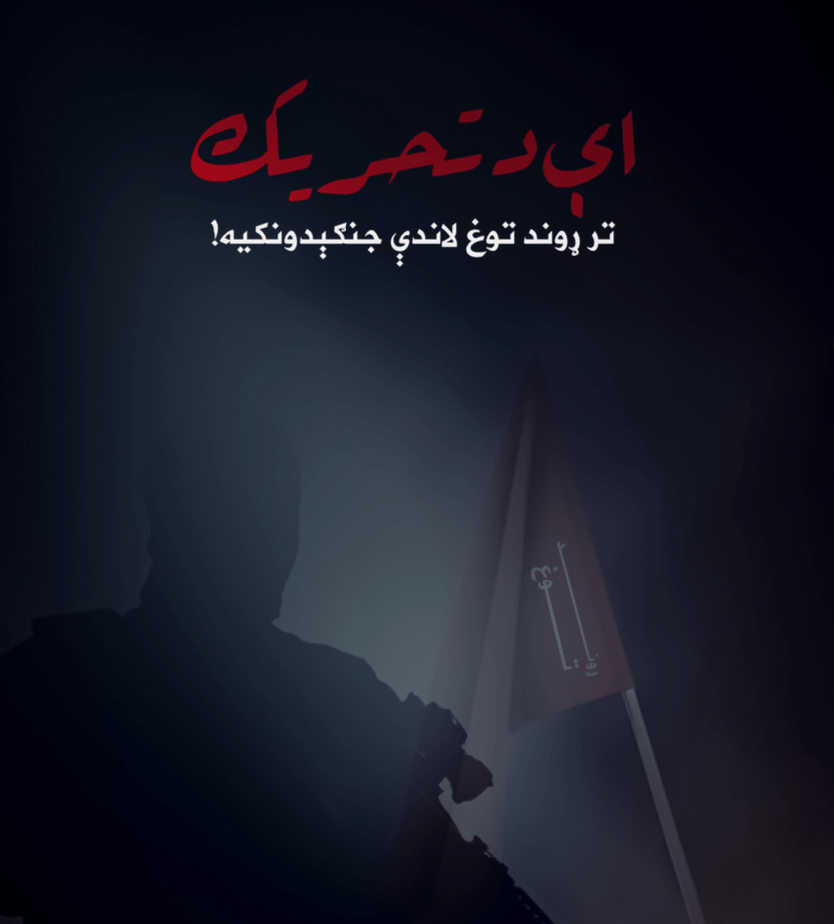

Legitimacy—not territory or tactics—is the battlefield here. In a new Islamic State–Khorasan Province (ISKP, Wilāyat Khurāsān) polemical pamphlet in Pashto, “O You Who Fight Under the Blind Banner of the Movement,” two phrases do all the work: the blind banner (al-rāyah al-ʿumayyah الراية العُمِّيّة) that renders rival fighting as pre-Islamic ignorance (jāhiliyyah[1]), and the oath of allegiance (bayʿah البيعة) that claims a monopoly on who may authorize violence.

The pamphlet is also a single treatise that constructs a theological case against “movement-ism” (ḥarakiyyah الحركية) and “nationalist” insurgency—above all the Afghan Taliban—by redeploying two well-known prophetic maxims. The first is the prohibition on fighting “under a blind banner,” which ISKP glosses as ʿaṣabiyyah (العصبية) (partisanship/tribal zeal) and, more broadly, fighting without a clear sharʿī aim or rightful leadership. The second is the obligation of bayʿah to a recognized Imam/Caliph, implying that only fighting conducted within a legitimate jamāʿah (community) and under a Caliphal chain of command qualifies as jihad. In ISKP’s telling, legitimate jihad is inseparable from tawḥīd (monotheism) and ruling by God’s law (ḥukm bi-mā anzala llāh), and obedience to an Imam is the gatekeeper of that legitimacy.

From this starting point, the ISKP builds a moral binary. On one side lies “true jihad,” anchored in tawḥīd, bayʿah, and obedience; on the other is “worldly militancy,” which it claims serves systems of kufr (unbelief) even when directed against declared enemies. The Afghan Taliban and Pakistan’s political order are placed firmly in the latter category. By insisting that these actors “ally with America and [its] friends,” ISKP frames their governance as collaboration with unbelief and prepares the terrain for takfīr (excommunication). The rhetorical effect is to strip rivals’ anti-occupation credentials of religious value before the doctrinal argument has even fully unfolded.

The next move translates that binary into a rule about means and ends. ISKP argues that tactical action—however costly or effective—cannot sanctify itself; fighting “against the unbelievers” fails as jihad if it is not nested within the Caliphate’s political frame. This logic, tethered to the “blind banner” ḥadīth, reclassifies Taliban battlefield deaths as “jāhiliyyah deaths,” severing the link between sacrifice and sanctity. In doing so, it undermines the Taliban’s stock narrative (“we expelled occupiers, therefore we’re legitimate”) by treating outcomes as irrelevant when the authority structure is wrong. The implied audience is clear: disillusioned fighters searching for a “purer” frame are invited to see their struggle as theologically null unless they transfer allegiance.

Read as strategy rather than sermon, the pamphlet’s center of gravity is authority. It seeks to reclassify rival militancy by making obedience under a caliphal chain of command the decisive criterion for legitimacy. Branding the Taliban’s flag a “blind banner” is a doctrinal relabeling maneuver that turns the Taliban’s own Islamic claims back against them: without bayʿah to a caliph, their fighting is recast as factional zeal ʿaṣabiyyah). This reclassification is reinforced by a hermeneutic toolkit—accusations of taḥrīf/taʾwīl (distortion/strained interpretation)—that primes readers to dismiss rival preachers’ cautions against takfīr as self-serving sophistry.

Having softened the ground, the ISKP broadens its target set. Pakistan is portrayed as a system based on human sovereignty—republican constitutionalism and “independent state” language—rather than revealed law. The Taliban’s rule is folded into the same indictment as a nationalist regime masquerading as Islamic governance. By collapsing Afghanistan and Pakistan into a single “apostate system,” ISKP dissolves jurisdictional limits and grants itself a cross-border mandate. The audience is encouraged to see the frontier not as a legal boundary but as an artificial line within the same moral problem set—an interpretive move that conveniently anticipates operational fluidity.

Only after these exclusions does the ISKP present its positive end state: the Caliphate as the sole legitimate governance framework. The canonical maxim—“whoever dies without a bayʿah dies a death of jāhiliyyah”—is treated as dispositive. Appointing a caliph is described as ḍarūrī (indispensable), tethered to Qurʾān and Sunnah and the vicegerency motif. ISKP then enumerates the prophetic pillars of collective life—samʿ wa-ṭāʿah (hearing/obedience), hijrah (migration), and jihad)—and explicitly attaches them to the Imam/Caliph, not to any national leadership. The point is not jurisprudential subtlety but organizational hegemony: ISKP seeks a monopoly on legitimate authority, such that all other banners are, by definition, blind.

In parallel, ISKP advances an anti-party ethic. It condemns dividing Muslims into bounded projects with “limited borders,” insisting that khilāfah (Caliphate) is a farḍ (duty) owed by the entire Islamic Ummah. Within this frame, a “movement” is not merely the wrong vehicle; the movement form itself is portrayed as contrary to prophetic governance. This anti-party populism—dressed in scholastic citations—serves as the normative bridge from doctrinal critique to organizational recruitment.

The closing pages of this publication convert doctrine into a call to action. Readers are urged to “rectify intention,” “be certain in the group’s purpose,” and “establish the Caliphate’s rule,” a pastoral-militant sequence designed to translate private misgivings into public bayʿah. True unity and victory, ISKP insists, exist only under the Imam’s banner [the Caliphate]; those who persist in partisan/national frames fight “for other than God.” The through-line from the opening claim to the final exhortation is consistent: authority first, tactics second.

Key Findings

- Authority, not target, is decisive: The core contest is not over whom to fight but over who may authorize fighting. Legitimacy is monopolized through bayʿah to the Caliph; other formations are relegated to “blind-banner” factionalism.

- Weaponized hermeneutics: Accusations of taḥrīf/taʾwīl (distortion) pre-empt de-escalatory counsels against takfīr and equip rank-and-file to rebut Taliban-aligned preachers.

- Border-collapsing frame: By recoding Afghanistan and Pakistan as a unified “system of kufr,” the ISKP dissolves jurisdictional limits, creating doctrinal cover for flexible targeting and intra-militant poaching.

Implications and What to Watch

- Recruitment wedge: The message targets disaffected Taliban fighters and Pakistan-facing networks, asserting that commanders’ alliances void jihad’s legitimacy and nullify martyrdom claims. Expect tailored outreach to mid-level cadres and prison populations where long-form doctrinal materials circulate.

- Category, not narrative, contestation: Because ISKP reframes rival jihad as jāhiliyyah via the “blind banner” category, counter-messaging that merely asserts Taliban piety is unlikely to succeed. The contest is over categories of legitimacy, not slogans.

- Operational signaling: The “apostate system” construction is a soft signal of cross-border intent. Watch for blended targeting justifications that mention Kabul and Islamabad in a single breath, and for increased use of bayʿah optics (pledge ceremonies, “I left the blind banner” testimonials).

Conclusion

ISKP’s pamphlet is an exercise in doctrinal boundary-setting. The ḥadīth of the blind banner and the obligation of bayʿah are mobilized as gatekeepers to legitimacy, shifting attention from battlefield performance to structures of authority. The core theme is apostasy by association: alliances—diplomatic, security, or governance—are treated as decisive outward proofs of unbelief, collapsing complex realities into bright-line categories useful for recruitment and coercion. By treating Pakistan and Taliban-ruled Afghanistan as components of a single apostate system, ISKP rhetorically abolishes jurisdictional limits and gestures toward operational diffusion along the frontier.

[1] Jāhiliyyah denotes, historically, the pre-Islamic era and, more broadly, a state of acting in ignorance of divine guidance.