This week’s al-Nabāʾ (issue 517) rests on two pillars: an editorial that issues an unambiguous veto on any “peace architecture,” and a weekly operations log centered on Africa and eastern Syria. Read together, the issue advances a single message: where negotiation proliferates, jihad—not governance—defines the path forward. Africa anchors the reported tempo, Syria functions as a low-intensity attrition front, and the editorial furnishes the doctrine that binds these dispersed actions into one strategy.

Framing the Hamas–Israel Ceasefire Track

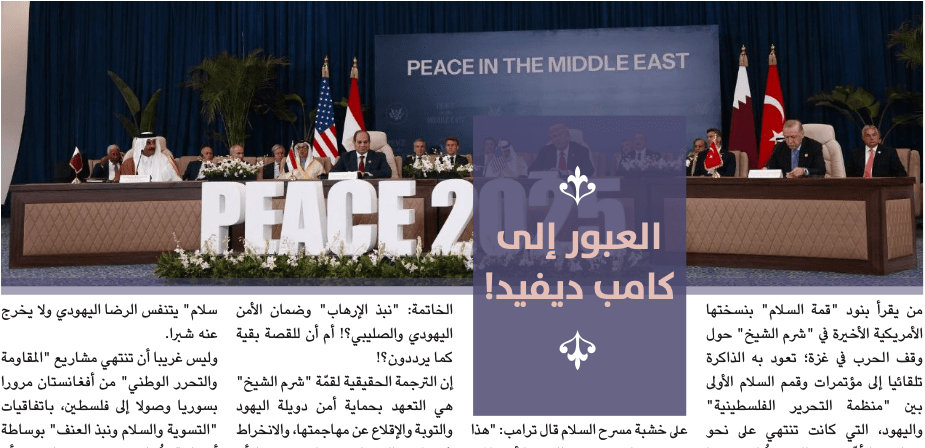

The editorial, “Crossing to Camp David!”, is a direct counter-narrative to the US-brokered ceasefire track at Sharm al-Shaykh. It collapses Oslo, Camp David, and Sharm al-Shaykh into a single script whose invariant outcome is Israeli security under international tutelage. Sharm al-Shaykh is cast as the latest iteration of that pattern—a pledge to protect Israel, repent of attacking it, and normalize relations—presented as a step many governments intended once the fighting subsided. By erasing distinctions among venues and timelines, ISIS urges readers to treat any diplomatic track as functionally identical and uniformly illegitimate.

Within this frame, proposals for a “transitional administration” or “peace councils” in Gaza are recast as guardianship over Muslim lands; participation therefore equals collaboration with the enemy. The veto is authorized by triangulating scriptural eschatology, historical memory, and present-tense guidance. An eschatological ḥadīth about fighting Jews is stitched to emblematic victories—Khaybar, Makka, Ḥiṭṭīn—to argue that when legal-diplomatic “traps” tighten, battlefield resolve, not negotiation, is the rightful response. The title’s “crossing” makes the thesis explicit: the legitimate path is the sword, not another Camp David. ISIS urges readers to “disbelieve in” alternative projects—nationalist pathways explicitly branded jāhiliyyah—and to view peace summits as factories of “more illusions.”

The editorial also insists that “the age of miracles is over,” grounding its call to arms in human agency: victory is produced through routinized violence—“the Prophet’s sword,” “his path”—carried forward “until the Hour.” A boxed quotation later in the issue functions as a doctrinal gloss: the conflict with Jews is religious, not national or territorial; legitimacy derives from the Book and Sunna, not international law, dismissed as jāhilī. The quote rehearses a selective historical indictment and declares that—even absent contemporary grievances—this would suffice as casus belli, before rejecting end-state formulas and invoking the “stone and tree” motif to sanctify an open-ended war. Read alongside the editorial, the quote hardens three claims: (1) diplomacy cannot resolve a creedal conflict; (2) international legal instruments carry no authority; and (3) a perpetual time horizon sanctifies attritional violence as ordinary proof of fidelity.

Rhetorically, this is a Strategic narrative in a Moral-Superiority register. Doctrinal certainty is fused with sacred and medieval exemplars to generate purpose while pointedly avoiding “governance” imagery. Jihad is positioned as the only authentic civic act under tutelage, pre-empting rival claims to represent “the people” through diplomacy, elections, or reconstruction councils. Internally, ISIS supplies an interpretive key that renders diplomatic churn as noise; externally, it widens the circle of “collaborators” to include clerics, notables, technocrats, and security auxiliaries who liaise with peace forums.

The policy implication is a portable veto. By conflating Oslo, Camp David, and Sharm, ISIS converts any forum into evidence that the same machine is at work—negotiations and participation in it reads as collaboration, resistance as fidelity.

Operational Updates

The operations section in issue 517 functions less as a catalogue of incidents than as a demonstration of repertoire. Across theaters, four recurring functions stand out: degrading state presence, policing social boundaries through sectarian violence, taxing local economies, and signaling organizational stamina—most prominently in Mozambique, the DR Congo–Uganda corridor, West Africa, eastern Syria, and Puntland.

In Mozambique, the presentation stitches together short, mobile raids, punitive village actions, and strikes on commercial nodes. The through-line is displacement and deterrence: houses and churches are burned to empty localities; a mining site is torched to impose costs on investment; police are described as “fleeing upon approach” to advertise local security vacuums. The same package includes daʿwa circuits—preaching tours into newly penetrated areas—signaling that outreach and intimidation travel together. The point is not governance provision; it is ingress legitimation under sacred cover.

In Somalia (Puntland), ISIS claims an ambush and a preemptive night “counter-attack,” with two local “leaders” among the dead—one military, one tribal notable accused of recruiting. The signal is deterrence toward brokers who liaise with authorities: engagement with the state carries personal risk.

The DR Congo–Uganda corridor reprises a familiar pairing: a punitive assault on Christian villagers and an ambush of uniformed forces on a key road segment. Photo documentation is flagged to buttress credibility—“we show what we say”—which matters for a wilāya that has often faced skepticism about claim inflation. The strategic effect is to shape movement corridors (through ambushes and roadside bombs) while keeping pressure on local communities ISIS frames as out-groups.

In Nigeria–Niger, West Africa Province leans on its signature repertoire: nighttime camp raids, interdiction of responding columns with IEDs, and harassment of auxiliaries. Spoils lists—rifles, machine guns, bikes—do reputational work, assuring fighters that materiel losses can be offset and that offensive initiative persists despite counterterror pressure. Taken together, the Africa theatre cultivate an image of operational breadth (multiple provinces active) and methodological consistency (raids, arson, road denial), rather than territorial consolidation.

In al-Raqqa and al-Khayr/Dayr al-Zūr, the claims emphasize quick strikes—IEDs, small-arms volleys, anti-material shots—against SDF/PKK personnel and logistics (including oil traffic). This is economy-of-force campaigning: persistence without resource burn, calibrated to keep security forces stretched and to contest the narrative that eastern Syria is fully pacified. The consistent labeling of opponents as “apostate PKK” preserves ISIS’s thesis that the SDF/PKK nexus—not the regime—is the proximate foe in its desert riverine zone.

Across theaters, victims are sorted with a stable lexicon—Christians, Crusaders/Westerners, apostates/local forces. That vocabulary does more than vilify; it supplies the rulebook for who may be killed, which assets may be burned, and when economic sites become fair game. It also explains why civilian harm and commercial sabotage sit so comfortably alongside ambushes of soldiers: all are rendered lawful within the organization’s boundary-making.

What the absence tells us? there are no governance photo-ops this week—no courts, clinics, or aid distributions. The closest substitute is daʿwa in Mozambique, which functions here as a soft edge for hard ingress, not as service delivery. That omission aligns the operations section with the editorial’s thesis: legitimacy flows from steadfast violence under a creedal banner, not from administering territory. The intended audience takeaway is that dispersed, modest actions still add up to fidelity—and that any local actor who engages peace infrastructure or reconstruction circuits may be reclassified as a legitimate target.

Policy Implications

Peace at stake: The editorial functions as a standing spoiler doctrine against regional de-escalation: by collapsing Oslo, Camp David, and Sharm al-Shaykh into a single “machine of surrender,” it installs a veto on diplomacy and recasts intermediaries as collaborators. Its political theology supplies the mechanism—mapping ceasefire venues onto a narrative of perpetual betrayal and instructing audiences and sympathizers that the only legitimate “crossing” is jihad and violence rather than negotiation—classic Moral-Superiority propaganda that offers meaning and certitude while binding small, dispersed operations into a coherent cause. The frame lowers moral and logistical thresholds for sympathizers to act against “peace infrastructure” (liaison bodies, reconstruction tracks, public advocates), and it explicitly threatens Gulf normalization with Israel by branding engagement as repentance and subservience. The net effect is to raise reputational and physical costs for expanding the Abraham Accords, deter fence-sitting elites, and incentivize opportunistic, small-cell violence that can claim doctrinal fidelity without central direction.

Operational implications: Issue 517 continues to position Africa as the locus of tempo—raids, road interdiction, punitive village actions, and economic sabotage—while eastern Syria is kept on a low-cost simmer against SDF/PKK personnel and oil logistics, and Puntland messaging deters intermediaries through selective violence. For policy circles, treat figures as claims and the sequencing as signal. Key indicators to track are the share of weekly claims by theater and tactic; the use of photo/video “proof” in the DRC–Uganda corridor; explicit mentions of notables, clerics, or recruiters in attack justifications; references to oil and transport nodes in Syria; and the continued absence—or sudden emergence—of governance imagery relative to daʿwa circuits. Read together, these patterns point to sustained harassment rather than territorial bids, elevated protection needs for intermediaries and commercial infrastructure in Africa, and persistent pressure on eastern Syria’s logistics.