Across November 2025, jihadist propaganda from the Islamic State, its Khorasan branch, al-Qa‘ida’s various affiliates, and aligned outlets presented a coherent picture of a movement under pressure and trying to solve several problems at once. The materials are not just a stream of communiqués and videos. Taken together, they show an ecosystem trying to harden doctrine, continue to move the center of gravity toward Africa, police its own internal boundaries, and fold Sudan, Mali, Gaza, and the Arabian Peninsula into a single story of assault on the Muslim Ummah. The result is a propaganda landscape where loyalty and geography are constantly being rearranged to keep the project alive after territorial loss.

Democracy as a Rival Religion and the Shrinking “Grey Zone”

One of the clearest threads in November is a renewed push to close any space for political pragmatism around elections and state institutions.

In al-Naba issue 522, the ISIS’s editorial on Iraq’s parliamentary elections reframes the entire electoral process as a religious faultline rather than a political event. Democracy is described as a system built on individualism, material gain, and party competition, contrasted with a “society of creed” ordered solely by monotheism and jihad. The true “winners” are not any Iraqi party but those who refuse to participate and persist in clandestine warfare; voters, candidates, judges, and soldiers securing polling stations are grouped together as “losers” who compete with God in legislation.

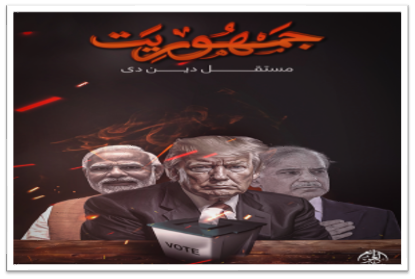

ISKP’s doctrinal treatise Democracy Is an Independent Religion pushes this argument further. It begins by redefining “religion” to include any structured system of obedience and law, then pulls democracy through that definition. Constitutions, parliaments, and electoral rituals are described as the institutional machinery of a rival creed. Voting becomes a ritual act of worship directed at a non-divine lawgiver; legislators are portrayed as competing divinities; courts are recast as temples of man-made law.

The publication then narrows two remaining escape routes. First, modern Muslim-majority states that adopt constitutions, recognize borders and entrench international legal norms are placed in a classical category of “refraining groups” against whom armed struggle is framed as continuous with earlier jurisprudence. Second, the doctrine of “excuse due to ignorance” is tightened so that most participants in democratic systems—from local councilors to civil servants—are held fully responsible for major disbelief.

This is more than rhetorical excess. It is a deliberate attempt to eliminate the “grey zone” that had previously allowed some supporters to rationalize tactical participation in elections or employment in state institutions. The practical effect is to lower the threshold for violence against polling places, courts, ministries, and even reformist Islamist actors who work within nation-state frameworks.

The Taliban’s own media, al-Sumud, sits in the background as an implicit rival project: it presents a nationalist-Islamist state with formal institutions and foreign relations November issue is organized around a sovereign “new Afghanistan” defended by martyrs’ blood and governed through recognizable structures. It foregrounds the foreign minister’s speech at the Moscow Forum, highlights press conferences by the government spokesperson and treats the recovery of Bagram airbase as “independence written in blood” and the humiliation of imperial greed. Across its pages, the Islamic Emirate is narrated as a normalized state with ministries, security agencies that provide regular briefings, and a foreign policy that engages regional forums. The jihad of the past two decades is re-coded as the founding war of a territorially bounded Islamic republic capable of managing airports, embassies, and diplomacy while keeping foreign troops out.

ISKP’s Democracy Is an Independent Religion positions itself directly against this storyline. The manifesto repeatedly describes the “current system in Afghanistan” as a contaminated form of democracy disguised as an emirate, pointing to the Taliban’s respect for national borders, issuance of passports, and engagement with the United Nations as evidence that they have accepted the architecture of the modern nation-state. The very attributes that al-Sumud celebrates—formal institutions, foreign relations, and the language of responsible governance—become proof that Taliban officials are administering a rival dīn. Judges, governors, diplomats and security forces are recast not as flawed Islamists but as custodians of the “religion of democracy” and therefore legitimate targets. The goal of this framing is to strip the Emirate’s project of Islamic legitimacy and to recode Taliban governance as another face of democratic unbelief, directly challenging any attempt to normalize Afghanistan’s current order.

Africa as the Main Theatre of Proof

The November issues of al-Naba continue to show that Africa has become the primary stage on which the ISIS proves it is still a fighting organization.

Al-Nabaʾ 521 already treated African provinces as the most dynamic fronts, highlighting persistent attacks in Nigeria, Mozambique, Somalia and the Sahel. The incident reports stress a pattern: ambushes on patrols, raids on outposts, the burning of vehicles and houses, and targeted assassinations of local “spies” and collaborators. The emphasis is on frequency and spread rather than on spectacular operations. The message is that these provinces are keeping up a steady grind that exhausts state forces and destabilizes rural life.

Al-Nabaʾ 522 continues this pattern. The operations section is effectively African: Nigeria, eastern DR Congo and Mozambique dominate the “harvest of the soldiers,” while Iraq and Syria recede into the background. The historic core of the ISIS caliphate remains symbolically central, but the dynamic proof-of-life now comes from elsewhere, namely Africa.

Al-Nabaʾ 523 goes further by treating Nigeria’s Borno and Yobe as the flagship front. The editorial on “a war between two projects”1 is accompanied by reporting that strings together multiple raids and ambushes into a single storyline. Casualty and equipment figures are almost certainly inflated, but they are used to argue that the “project” is still capable of killing, capturing, burning, and seizing in ways that embarrass national armies.

A parallel move appears in al-Qa‘ida’s orbit. The Ṣadā al-Thughūr November newsletter aggregates operations from al-Shabāb in Somalia and JNIM-linked forces in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. Infographics present counts of raids, IED attacks, assassinations and captured weapons over a lunar month. The details are selective and framed, but the pattern is clear: Africa is presented as a continuous belt of momentum where jihadist factions harass state forces and foreign contingents with relatively low-cost operations.

JNIM’s separate statement on massacres in Mali complements this by focusing on victimization rather than on numbers. It chronicles killings and displacement attributed to the Malian army and its partners, including Russian contractors, and casts jihadist factions as the only reliable armed defenders of Muslim communities. That narrative is designed to justify recruitment and local cooperation as acts of protection rather than aggression.

November propaganda materials continue to re-center Africa in the jihadist imagination. Even if operational realities are more fragmented and locally driven than the propaganda suggests, the effect is to shift attention and resources away from the Levant and toward Nigeria, Somalia, the Sahel, and Mozambique as the main theatres of “effective” jihad.

Policing the Field: No Safe Third Way

A third major concern running through November’s propaganda is internal boundary management, distinguishing the “true” project from rival Islamist actors, former allies and reformist currents.

Al-Nabaʾ 521 casts comparison between Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and Abu Muhammad al-Jolani. Jolani, the leader of Hayʾat Taḥrīr al-Shām (HTS) in northwest Syria, is used as a contemporary example of a figure who rose from the jihadist milieu only to become a custodian of a post-caliphate order aligned with hostile powers. The point is to remove any residual ambiguity about HTS. It is not a legitimate rival movement but part of the system that must be destroyed.

Al-Nabaʾ 523 sharpens this into a categorical dichotomy. The world is said to be witnessing a war between only two projects: the project of those who fight ṭāghūt everywhere and the project of those who defend ṭāghūt under various names and banners. The harshest language is directed not at Western governments but at those who once praised ISIS and now criticize it or join its rivals. These figures are described as people who believed and then disbelieved, now working to block others from joining the jihadist project.

A short religious text in the same issue offers a typology of people who abandon jihad at different stages when hardship intensifies. It is a subtle form of Guidance-oriented discipline: fighters and supporters are invited to see any doubt, fatigue or inclination toward compromise as the first step toward a shameful category of deserter.

ISKP extends this boundary work to the Taliban. By classifying Afghanistan’s current system as a version of democracy dressed in Islamic language, it places Taliban officials, judges and security forces in the same doctrinal category as rulers historically treated as legitimate targets. There is no room for viewing the Taliban as an “Islamic government with flaws.” In this narrative, they are guardians of a rival religion.

Within al-Qa‘ida’s Yemeni milieu, the polemical essay on Riyāḍ Bin Shaʿb2 performs an analogous function. Using the testimony of Muḥammad Muʿawwaḍah as a spine, the text portrays Riyāḍ as a figure who moved from claiming to reform jihad to embracing projects of corruption and collaborating with Saudi and Shia forces. Organizational setbacks, leadership losses and security breaches are retroactively explained as the result of his deviation rather than of AQAP’s own strategic missteps. The intended lesson for the base is that “reformist” paths are treacherous: they end not in a purified jihad but in betrayal and alignment with the enemy.

Even AQAP’s statement response to the Marib security services, which accused it of involvement with a Houthi cell, is framed as an internal reassurance. The group insists that alliance with the Houthis is religiously impossible after years of fighting them, invokes classical doctrinal language, and presents itself—as well as local tribes—as a barrier that has prevented Houthi expansion into Marib’s plains and highlands. It claims to have limited its operations to avoid harming a governorate full of displaced people, while simultaneously denouncing the local government complex as a joint war room for Americans, Israelis and Arab coalition partners.

This pattern included in November materials collectively narrow acceptable positions inside the jihadist universe. There is no legitimate “third camp” between uncompromising jihad and outright apostasy. Reformist tendencies, tactical pragmatism, and local ceasefires are framed as the first step down a slope that ends in treason.

Sudan, Mali, Gaza: Stitching a Single Wound

If doctrinal texts fix the rules and internal lines, another theme in November materials tries to reframe current crises as expressions of one continuous assault on the Muslim Ummah.

The AQAP statement on Sudan is the clearest case. It takes massacres in al-Fāshir and other parts of Darfur as its starting point, but quickly subsumes them into a larger plot attributed to “Arab Zionists” acting on behalf of Israel and Western capitals. The United Arab Emirates is elevated as the key architect, described as the “mini-Zionist state” and the most devoted executor of a project to reshape the region.

Sudanese actors themselves are largely erased from the frame. Responsibility for killings and displacement is pushed upward onto a transnational axis running from Tel Aviv and Washington through Abu Dhabi. The war in Sudan becomes one more theatre in a continuous attack that includes Gaza, Yemen, and Libya. This flattening serves an organizational purpose: it justifies treating Emirati assets as priority targets far from any Sudanese battlefield.

The same issue presents the AQAP attack on the government compound in al-Mahfad, Abyan, as the direct operational response to this diagnosis. The target is depicted not simply as a Yemeni base but as a command center for Emirati-backed forces and their drones. The attackers are cast as answering the blood of Sudanese and Palestinian civilians by hitting the “hand and eye” of the conspirators on Yemeni soil.

JNIM’s statement on massacres in Mali provides a Sahelian complement. It sets out a narrative of systematic state and foreign violence against Muslim villagers, using this to justify jihadist operations as protective rather than aggressive. When read alongside the Sudan statement, a shared structure appears: state forces and their allies are portrayed as perpetrators of mass violence against Muslims; jihadist groups present themselves as defenders; and widely separated crises—from Darfur to central Mali to Gaza—are folded into a single “forgotten wound” narrative.

For external actors, the point is not to grant these stories credibility but to recognize their function. Atrocities and abuses by state forces, militias, or foreign contractors are quickly woven into this transnational script. The propaganda use of Sudan and Mali indicates a direction of travel: attacks on Emirati, Western, or Russian-linked interests in Africa and the Arabian Peninsula are increasingly framed as defensive responses to crimes committed elsewhere.

Media Infrastructure and Decentralized Amplification

None of these themes travels without infrastructure. November’s material shows continued investment in decentralized but branded media ecosystems.

The Ṣadā al-Thughūr newsletter includes a concise guide to using Rocket.Chat and announces the creation of “media front cells.” These are described as loose networks of sympathizers responsible for receiving official releases, archiving them, and pushing them across smaller channels to “break the media blockade.” The guidance emphasizes disciplined communication: clear channel naming, concise posts, use of threads, minimal unnecessary mentions, and two-factor authentication.

The direction of travel is clear. As large social media platforms become more restrictive, propaganda work moves into fragmented, semi-closed ecosystems, and supporters are asked not just to consume content but to act as semi-professional distributors, and archivists.

What This Snapshot Tells Us

November’s propaganda does not introduce a single breakthrough narrative; it consolidates and connects several trends that have been building for some time.

- Doctrinally, democracy is reframed not as flawed politics but as a rival religion. From Iraq to Afghanistan, it is treated as a separate dīn whose institutions, rituals and personnel are engaged in shirk. The space for “ignorance” or “compulsion” as excuses is narrowed, expanding the pool of permissible targets and complicating electoral processes, political inclusion and the reintegration of ex-combatants. These materials should be read as a guide to future attack planning, not only as rhetoric.

- Intra-jihadist rivalries are deepening, particularly in the Sahel and Yemen, alongside a harder internal policing of boundaries. ISIS media seeks to erase JNIM’s ideological standing; JNIM presents itself as a protector of civilians against state and rival abuses; AQAP uses polemics to offload blame onto individual leaders. Reformers, defectors, pragmatic Islamists, and rival factions are portrayed as sliding quickly into collaboration with enemies. These dynamics create both openings and risks: exploiting fissures may constrain the most uncompromising actors, but overtly backing one side can entrench armed governance and endanger mediating figures.

- Geographically, Africa continues to move from periphery to center in how both ISIS and al-Qa‘ida networks prove their continued relevance. Operations in Nigeria, Somalia, the Sahel, Mozambique and Central Africa are used as weekly “evidence” of momentum, even when the underlying insurgencies are fragmented and locally driven. Strategic communication and security planning can no longer treat these fronts as secondary while focusing on the Levant, yet it remains essential to resist the groups’ narrative flattening: not every actor flying an ISIS flag is equally central, and heavy, undifferentiated responses risk reinforcing the image of a single, centrally directed global war.

- The confessional genre remains a double-edged tool. Testimonies from captured or repentant militants can illuminate recruitment pathways, organizational cultures, and patterns of violence, but they also strengthen narratives of inevitability and can be appropriated by armed groups themselves. States and international actors that lean on confession-centric messaging should assume that jihadist media strategists are watching and will adapt accordingly.

- At the level of grievance, crises in Sudan, Mali, and Gaza are increasingly stitched into a single story of sustained assault on the Muslim community, with the UAE and other external actors cast as central orchestrators. This cross-theatre framing is likely to influence target selection in ways that ignore national borders.

- Finally, the media landscape is being tuned for a long campaign conducted from dispersed fronts, relying on decentralized distribution and archival networks rather than a small set of major platforms.

Taken together, November’s propaganda is less a collection of isolated statements than a coordinated effort to rebuild a damaged project on new terrain. The tightening of doctrine around democracy, the re-centering of Africa as the main arena of “effective” jihad, the aggressive policing of internal dissent, and the stitching together of Sudan, Mali, Gaza, Yemen and Afghanistan into one continuous wound are all strategies for managing loss. They offer supporters a moral map in which compromise is equated with betrayal, elections are recast as a rival religion, African fronts supply proof of vitality despite reversals elsewhere, and almost any atrocity by state or foreign forces can be folded back into a single narrative of persecution and justified revenge.

For policymakers and observers, the implications run in two directions. These materials need to be treated as strategic texts that signal where actors are trying to move their base, which theatres they seek to elevate, and which adversaries they are promoting to the top of the target hierarchy. At the same time, there is a need to avoid reinforcing the binaries the propaganda is working so hard to construct. Undifferentiated military responses in African theatres, partnerships with abusive local forces, purely symbolic engagement with elections, or uncritical normalization of authoritarian state projects will tend to confirm, rather than undercut, the stories these groups are telling.

Reading November’s output carefully is therefore not simply an exercise in monitoring extremist media; it is a reminder that external choices about law, security, and diplomacy can either narrow or widen the space in which these narratives resonate.

- The lead editorial of issue 523 of the ISIS’s weekly Arabic newsletter al-Nabaʾ, which argues that only two meaningful “projects” exist in the world: ISIS’s project of fighting ṭāghūt (idolatrous, tyrannical rule) everywhere, and a rival project that defends ṭāghūt under various banners. The text expands the enemy camp to include not only states and “original disbelievers” but also former sympathizers, rival jihadist factions and reformist Islamists, depicting them as people who “believed and then disbelieved” and now collaborate—overtly or implicitly—with hostile powers. The binary is used to erase any legitimate “grey zone,” recast defections and criticism as a form of apostasy, and present continued loyalty to ISIS as the only valid option. ↩︎

- Riyāḍ Bin Shaʿb is a Yemeni Islamist activist and former AQAP-adjacent figure whom al-Malāḥim Media’s Shāhed service singles out as a cautionary example of “deviation.” The release portrays him as having moved from claiming to “reform” jihad to embracing “projects of corruption,” seeking financial backing from Saudi and other state actors, obstructing the work of militants, and, through his choices, allegedly contributing to security breaches and the killing of fighters. It uses the confession of Muḥammad Muʿawwaḍah to frame Riyāḍ as a symbol of how internal critics slide, in AQAP’s narrative, from dissent into collaboration with hostile governments. ↩︎