There is a common, comforting belief that American democracy is safe: it is old, the country is wealthy, and decades of political science research suggested that rich, established democracies simply do not die. And yet, as we watched a violent insurrection unfold on January 6, 2021—just one day after a historic election in Georgia showcased the promise of a multiracial democratic future—that illusion of safety was shattered.

The numbers often cited to capture this retreat are sobering. Freedom House, which tracks the health of global democracies, gave the United States a score of 90 out of 100 in 2015. By 2025, that score had fallen to 83—lower than several new or historically troubled democracies. Whether one agrees with every component of those indices or not, the direction of travel is hard to ignore.

In Tyranny of the Minority, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt challenge the most reassuring assumptions head-on.[1] Their claim is not simply that democratic backsliding is real, but that the American version is distinctive among peer democracies: its roots run through party incentives, historical conflicts over inclusion, and institutions that can translate narrow advantages into durable rule. The unsettling part is also the most analytically useful: democracies can rot from the inside while elections remain on the calendar and legality remains the language of power.

The next five takeaways are less about dramatic breakdown than about quiet drift: how ordinary actors, using ordinary tools, can make democratic erosion look lawful, reasonable, even routine.

1) Losing is a skill—and some parties are forgetting how to do it

As the political scientist Adam Przeworski memorably put it, “Democracy is a system in which parties lose elections.” That line sounds almost trivial until you take it seriously: accepting defeat is a learned norm, and it is the hinge that makes peaceful transfers of power possible.

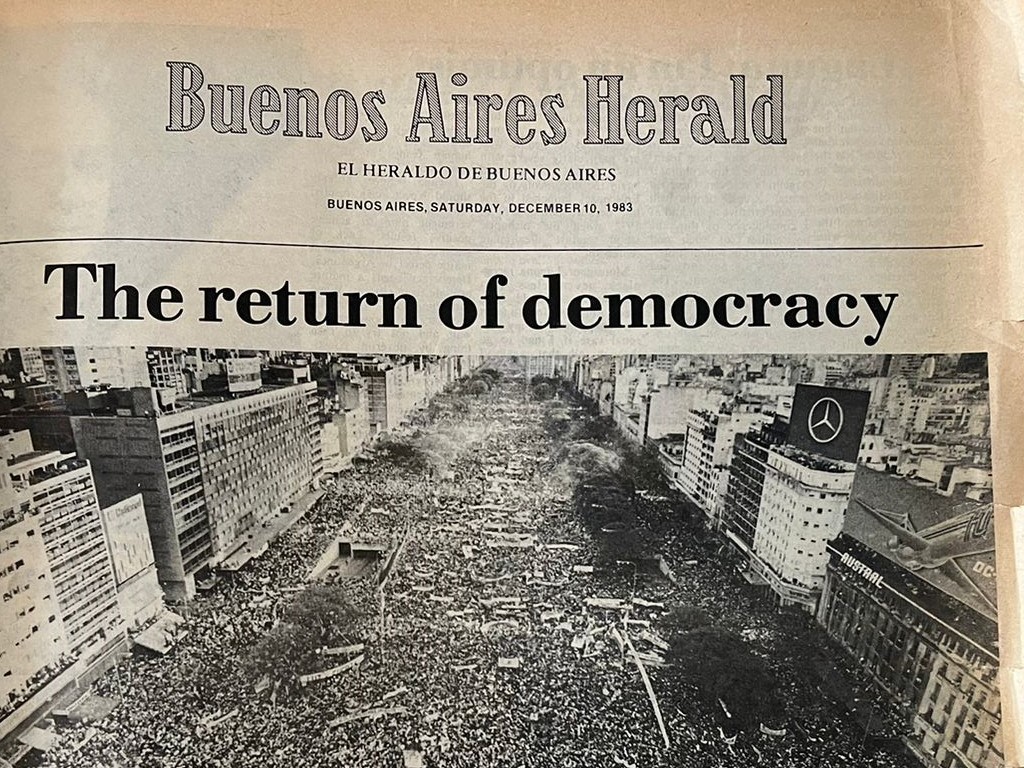

A model of how this norm can hold under stress appears in Argentina in 1983. After a decade of military rule, the powerful Peronist party lost a free election for the first time in its history. The party’s leaders accepted the result, congratulated the winner, reorganized, and adapted—then went on to win subsequent presidential elections.

The contrast matters because Levitsky and Ziblatt are interested in the opposite trajectory: what happens when parties develop an outsized fear of losing. That fear often takes shape when a dominant group interprets social change as status displacement rather than routine political competition. Their Thailand example makes the mechanism vivid. For years, the middle-class-based Democrat Party championed democracy. But after repeated defeats by a party that mobilized the country’s poorer, rural majority, their commitment wavered. The Bangkok elite came to treat equal political voice as illegitimate—less a policy dispute than a violation of hierarchy. The move from “we lost” to “the system is broken” became the opening for boycotts, legal obstruction, and eventually support for the 2014 military coup.

If democracy rests on loser consent, this is the nightmare scenario: defeat stops being a temporary setback and becomes proof that the game itself must be stopped.

2) Democracies aren’t usually killed by dictators alone, but by “respectable” enablers

Who makes death of democracy politically feasible? Levitsky and Ziblatt argue that violent extremists and would-be authoritarians rarely succeed on their own. They need accomplices inside the system—mainstream politicians who appear to play by the rules while quietly enabling assaults on democracy. They call these actors “semi-loyal” democrats.

The interwar France case is warning shot. After right-wing militias assaulted the French parliament on February 6, 1934, the decisive variable was not only the street violence, but the reaction of France’s leading conservative party, the Republican Federation. Instead of isolating the extremists, party leaders tolerated them, defended them, and helped launder their actions into patriotic legitimacy.

Semi-loyal politicians stand in contrast to “loyal democrats,” whom are those who meet the real democratic test: disciplining extremists on their own side. The toolkit is simple and sharp:

- Expel extremists from your ranks.

- Sever ties with anti-democratic groups.

- Condemn violence committed by your side—unambiguously.

- Join forces with rivals when needed to isolate extremists.

The counterexample is Spain in 1981. When military officers attempted a coup, leaders across the political spectrum publicly united to defend the constitutional order, isolating the plotters and raising the costs of further escalation. The sociological lesson is not that Spain had better people. It is that elite gatekeeping—who gets normalized, protected, and rewarded—can decide whether extremism becomes an acceptable political tool.

3) The modern autocrat’s playbook is “constitutional hardball”

The most dangerous threats to democracy often arrive with legal documents, not tanks. Levitsky and Ziblatt use “constitutional hardball” to describe a pattern: using the letter of the law to violate its spirit—technically legal moves that corrode fair competition.

They highlight four recurring forms:

- Exploiting gaps: weaponizing ambiguities in rules for partisan gain.

- Excessive use of legal power: pushing lawful tools to destructive extremes.

- Selective enforcement: applying rules harshly to opponents while ignoring allies.

- Lawfare: crafting seemingly neutral laws designed to weaken rivals.

Hungary under Viktor Orbán functions as a modern illustration because the steps are formally legal but cumulatively regime-altering: constitutional rewrites, judicial capture, media control. The crucial point is not only that this can happen “legally,” but that legality itself becomes camouflage. opponents can be painted as hysterical or partisan for treating lawful acts as authoritarian.

This playbook is not foreign to American political development.

4) America has done this before: the violent overthrow—and legal consolidation—of multiracial democracy

Many Americans assume democratic collapse is something that happens elsewhere. This is historically false. Reconstruction is presented as America’s first serious experiment in multiracial democracy: expanded Black political participation, competitive elections, and substantial numbers of Black officeholders across the South.

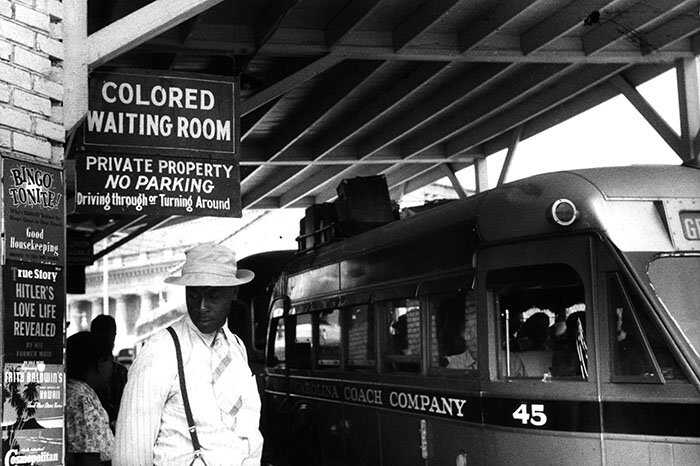

That democratic opening triggered a backlash that combined coercion and law. The initial phase involved terror and intimidation. The next, more durable phase used legal engineering—poll taxes, literacy tests, and other devices designed to circumvent the Fifteenth Amendment’s ban on racial discrimination while achieving racial exclusion in practice. The point is not only that violence mattered; it is that violence alone is unstable. Durable domination required rules that made exclusion repeatable and “normal.” The Supreme Court’s refusal to effectively protect Black voting rights—exemplified in the 1903 Giles v. Harris decision—helped lock in disenfranchisement. In a parallel, federal voting rights legislation (the Lodge Bill) passed the House but was blocked in the Senate, removing one of the last institutional obstacles to the establishment of Jim Crow’s long authoritarian order in the region.

If we would call a regime authoritarian elsewhere under these conditions, we should not soften the label when the case is “home.”

5) Our Constitution was built to fetter majorities—and those constraints now have a partisan edge

The final discomfort is institutional, not psychological. Levitsky and Ziblatt argue that many Americans treat the Electoral College, equal state representation in the Senate, and other counter-majoritarian features as a coherent blueprint for balanced government. Their claim is that these features were often messy compromises designed to placate powerful minorities at the Constitutional Convention—especially small states and southern slave states.

The South’s determination to protect slavery shaped representation and national power. Equal representation in the Senate served small states, even as major framers warned it would empower a “small minority” to thwart majority rule. Minority vetoes do not remain neutral over time. As parties become geographically and demographically sorted, counter-majoritarian institutions can acquire a consistent partisan bias—making it structurally easier for one coalition to wield power without winning majority support.

The filibuster crystallizes this dynamic. It is not in the Constitution at all, yet it evolved into a routine supermajority requirement that can function as a minority veto over ordinary legislation. This is not an abstract design quirk; it is a live pathway through which minority rule becomes politically sustainable.

Institutions will not save democracy—we will

The core warning of Tyranny of the Minority is that the threat to American democracy is not reducible to one person or even one moment. It is rooted in incentives that make losing feel catastrophic, in elite choices that normalize extremism, and in institutions that can convert minority advantage into durable rule.

If democracy is a fragile social arrangement, then it survives only when citizens and elites treat it as something to actively defend—especially when defense is inconvenient.

One final question to sit with: if a political system increasingly rewards winning without persuading majorities, what has to change—norms, institutions, or both—for democratic competition to become tolerable again?

[1] Method note: This post draws on Levitsky, Steven and Daniel Ziblatt. 2023. Tyranny of the Minority: Why American Democracy Reached the Breaking Point. New York: Crown.